CHAPTER ONE - Early Concepts of the Building

In June of 1919 a joint NAS and NRC Committee on Building Plans was appointed to oversee the design of the building. The original committee membership consisted of Academy members Hale, Walcott, Noyes, Dunn (appointed to act as advising engineer to the project), and Millikan, along with National Research Council members J. C. Merriam and James Angell. At a meeting in December of 1919 the group stated its vision of the building's function and character, specifying “two definite elements”: First, it should be monumental, in order to “serve as center and symbol of American scientific research.” Second, it should meet the Academy's and the National Research Council's needs for office and exhibit space, as well as contain a library and “anything else deemed necessary.”2

Henry Bacon's Neoclassical Lincoln Memorial, which was still under construction when the Academy building was being planned, was a key element in the realization of the McMillan Plan. The Commission intended it to serve as a “frame” for subsequent development in the area, calling for “the continuation along B Street of semipublic buildings architecturally in harmony with the Memorial.” Thus in the Commission's view, architect Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue's design should incorporate strong elements of classicism in order to harmonize with the Lincoln Memorial's Doric colonnade and overall appearance, a direction that was disagreeable to Goodhue and that led inevitably to conflict.

|

|

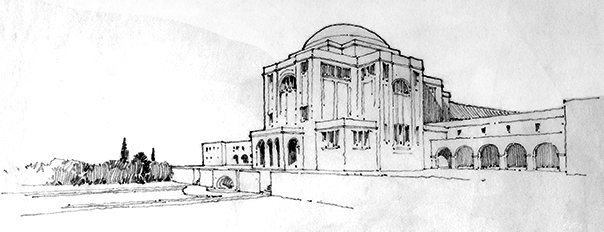

Goodhue preferred to produce a “building of the irregular character” that would be “practical and convenient without regard for symmetry.” Nevertheless, given the constraints inherent in the B Street site, he created a plan for a building he described as shaped as “a hollow square” with a center rising “in the form of a Greek cross with domed ceiling.” Although the Academy's reaction to the plans appears to have been mostly positive, Goodhue recalled being asked to add a Corinthian colonnade to the façade, an unwelcome suggestion he described as “the last straw.” A compromise of sorts was worked out, specifying that Goodhue would design a classically-informed building that he described as being “an interesting variant of, though by no means out of harmony with, the prevailing style of Washington architecture.” He then proceeded “rather downheartedly” to draw up the plans.

On March 26, 1920, Goodhue, accompanied by Angell as a representative of the Academy Building Committee, met with the Commission on Fine Arts to submit his drawings. To Goodhue's dismay, the Commission was dissatisfied with the plan, particularly with its design of the main façade, and as Goodhue recalled it, they wanted him to “try again, and to be more classic.” Goodhue did not take kindly to the suggestion. Neither did Angell, who declared himself “extremely irritated” with the Commission's actions and whose “personal disposition” was “to invite this entire crowd to retire to regions where the temperature is said to be permanently uncomfortable.”3 A standoff ensued, until finally at its May 12, 1921 meeting, the Commission approved a slightly revised version of the Academy's plan for its building.

Ground was broken in the first week of July 1922. Because part of the building site had once been a stream bed, elaborate steps had to be taken to secure the foundations. Seventy-four square concrete piers, each five feet on a side, were sunk to bedrock to shore up the reinforced concrete girders supporting the walls; the girders supporting the marble terrace were set on 33 large steel tubes that were driven to bedrock and filled with concrete. The bedrock under the once-submerged southeast corner of the site was encountered at thirty-seven feet below ground, as compared to a depth of only four feet for the northwest corner.4

|

|

|

The cornerstone was laid in October of 1922. After nearly two years of construction, the building was completed and dedicated on Monday, 28 April 1924, just in time for the first day of the Academy's Annual Meeting that year.

The dedication was described in the Academy's Annual Report as “simple but impressive,” and was attended by more than 600, including 106 of the Academy's membership of 210 at that time, as well as members of the Cabinet, Congress, the diplomatic corps, and representatives of the Carnegie Corporation of New York. After brief addresses delivered by Academy Vice President J. C. Merriam, NRC Permanent Secretary Kellogg, and Gano Dunn, head of the NAS Building committee, the principal address was delivered by President Calvin Coolidge, who referred to the building as a “Temple of Science.” The day after its dedication, the building was opened to the public.5

|

|

The Academy now had an appropriate home, a building for the NAS and NRC, with enough space to conduct the NRC's work6 and to serve as the gathering place for the membership of the NAS. In retrospect, the building sits on a marvelous site, within view of the memorial dedicated to President Abraham Lincoln, who signed the charter document creating the National Academy of Sciences.